|

Artists

bring Nativity to life posted 12/24/99 By Joan Altabe

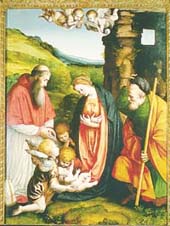

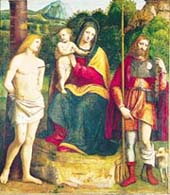

They could be pictures in your family photo album: Madonnas in Renaissance paintings. Artists of the 15th century envisioned Holy Mothers as earthy types. Yet seeing them can put you in a devotional mood -- the mood of Christmas. Their naturalness heightens the sense of exaltation. No stiff, flat, unfeeling medieval Madonnas, these Renaissance Marys. No enthroned figures set against a background of gold, holding their infants like sports trophies. Renaissance painters told the story of divine devotion as if Mary were your next-door neighbor. In "The Holy Family with A Donor" by Gaudenzio Ferrari, in Florida's Ringling Museum, you can see the Family's fingernails, and those of the Donor, too. Even nails on the tiny feet of the infant show clearly. So do the nostrils of a donkey and cow hidden in shadow, as well as the grain of wood in an arbor in which they stand. Mary's head is pitched forward, her eyes fixed on the infant at her feet, her arms cupped in a cradling gesture, all signals that the infant is hers. Her watchfulness is the picture of an anxious mother; although her mouth, which is in repose, gives her a less dreading, more adoring air. As you follow Mary's absorbed gaze to her infant, you also become engrossed in him. The infant, looking up at his mother with hands outstretched, like all babies who want to be held, holds you in the scene. All of this sharpens your impression that you're looking at a picture of a real woman. She interacts with her baby. She feels, and you do, too. You experience a similar emotion looking at "The Virgin Child with St. Benignus and St. Placidus" by Domenico Puligo, in which the infant, again like any baby, squirms on his mother's lap. In turn, the Madonna, again a typical mother, holds one of his wriggling legs with a fond hand. The image of Joseph kissing the feet of Mary's child in "Madonna and Child with St. Joseph" by Bernardino Zaganelli, is less venerating and more loving than all the Josephs held in Gothic cathedral stained glass. And Mary is no imperious, expressionless queen acting dutifully. But in this family portrait, you know ahead of time how things turn out. This makes the story that the Ringling Madonnas tell more affecting. You look at the child's pudgy hands and see them as an adult's pierced by nails. You look at Mary holding her child and see her holding her crucified son in Michelangelo's "Pieta" -- no longer well-fed, but wasted; not dozing, but dead. Renaissance painters knew what they were doing when they brought Mary to life. They brought Christmas to life, as well, with their naturalistic treatment of the holy family. If it weren't for the Renaissance and its emphasis on the individual, all Nativity paintings would look alike. Beginning in the 14th century, painters began taking great liberties in their freewheeling accounts of the biblical story. Churchmen also made a difference at about this time. The Catholic counter-Reformation movement, seeking converts from a population that couldn't read, commissioned artists to paint religious scenes that made strong emotional appeals. Three works at the Ringling, all with the same title, "Adoration of the Shepherds," are testaments to the poetic license in paint that resulted. Even though the Bible says the birth of Christ took place at night, Ludovico Mazzolini, known for his sun-bright colors, rendered the scene in daylight. Jacopo Bassano, celebrated for picturing religious subjects in earthy ways, put shepherds into the birth scene. And while Luca Giordano is notorious for copying other artists' styles, his is the only portrayal in the group that placed Christ's birth toward the back of the picture. Perhaps one reason the scene has been subject to so much variation is that the story of the Nativity, as told by Luke and Matthew, was very short on detail and inconsistent, one from the other. Matthew, author of the first gospel, told of wise men from the East who followed a star, bearing gifts for the new lord. Luke, however, spoke of an angel leading shepherds to Jesus. In embellishing, some artists changed the wise men into kings with attendants in tow. Though Luke never wrote of such things, some showed the shepherds bearing touchingly lowly gifts, such as poultry, milk and eggs. Portrayals of Mary kneeling in adoration, as seen in Mazzolini's work, also are plays of artists' imaginations. Byzantine artists even pictured Mary on a bed with two midwives attending her. Then, when Giovanni de Caulibus, a follower of the Franciscan Order in the 14th century, wrote in his "Meditations" of Mary giving birth leaning against a pillar (symbol of spiritual strength in Revelations), artists began to depict her in that posture. Mary is not leaning against a pillar in Mazzolini's work, but he includes two pillars anyway. Mary also is shown as a blonde dressed in white in Giordano's work, perhaps due to the writings of St. Bridget of Sweden in the 14th century in which she described a vision of Mary in white cloak and golden hair. As if to complete the Hollywood-ized version of the Nativity, another rendition at the Ringling Museum -- this one by Bernardino Lanini -- shows Mary not only dressed in celestial blue and golden robes (hardly the outfit for riding on a donkey), but accompanied by an angel playing a violin. No matter the differences, these paintings all say the same thing: Merry Christmas. |