click to enlarge |

|

A Bacchanal

Luca Giordano “Wine, Women and Song”

Docent to Docent Presentation,

January 29, 2008

by Lin Vertefeuille |

I. Introduction

The usual depiction of a bacchanal with “wine, women and song” is a physical

manifestation of a profound context of worship which has influenced visual, performing

arts and literature through the ages. Bacchanalia is a subject worthy of representation in

art, but often misinterpreted from our contemporary viewpoint. Luca Giordano’s

painting is more clearly understood by exploring the subject of Bacchanalia and its Cult

of Dionysus. This requires us to examine Dionysian mythological origins, bacchanal

iconography, history, the reality of its spiritual importance and religious practice. It

is my expectation that a broad comprehensive approach will give an appreciation of the

bacchanal theme and provide specific information to be used in interpreting Luca

Giordano’s painting. I hope Luca Giordano’s wonderful Bacchanal will be

understood and most of all enjoyed.

II. Terminology

Bacchus and Dionysus are interchangeable names of the same deity. Bakchos

was his common Greek name and his followers were called Bacchoi. The Roman

adaptation was Bacchus. Dionysus also derived from Greek was a term for

“son of Zeus.” The Cult of Dionysus and the rites of his mysteries were

practiced in both public festivals and in more secretive bacchanals.

III. Mythological Origins of Dionysus

Dionysus’ birth was very strange even for a mythological deity. He was conceived in a

sexual relationship between Zeus and the mortal, Semele, daughter of Cadmus, King of the

Greek city of Thebes. Zeus made a passionate but irrevocable vow to grant her any wish.

Hera, the vindictive wife of Zeus, used his vow as an opportunity to destroy her. She

tricked Semele into wishing to behold her lover, Zeus, unaware that mortals could never be

allowed to see him. When Zeus appeared in a thunderbolt, Semele was instantly consumed by

fire and sent into Hades. At the moment of her destruction, Zeus took her undeveloped

child, Dionysus, and placed him on his thigh to complete his gestation. After he was born

(again) Zeus gave the infant Dionysus to Hermes to hide from Hera’s wrath. Hermes

placed Dionysus into the nurturing care of the gentle Nymphs of Mt. Nysa.

It was said that later in gratitude Zeus placed the Nymphs in the sky as the star group Hyades

and when they appear near the horizon, they bring gentle rains that nourish grapes.

Dionysus invented cultivation of grapes and wine. He was tutored by an aged satyr,

Silenus, who remained his closest companion. Dionysus traveled the world spreading

viticulture and viniculture and the mysteries of his worship.

IV. Mythological Tales of Dionysus

There were tales of his travels that illustrated his benevolent nature. In one story he

went on a dangerous journey into the underworld and led his mother, Semele, out of Hades

(raised her from the dead) so she could dwell in Mt. Olympus.

In another episode, Ariadne, daughter of the Minoan King who helped Theseus escape the

labyrinth, was abandoned by him when she fell asleep on the Island of Naxos. Dionysus

found the desolate Ariadne and feeling compassion, feel in love and rescued her. Dionysus

and Ariadne were popular romantic subjects for artists. Note the ormolu clock of

“Sleeping Ariadne” in Ca d’Zan.

During Dionysus’ travels when people rejected his worship he could be a god of cruel

retribution. The story of Pentheus in Euripides’ play, Bacchae, related the most

horrific punishment in all Greek mythology. Dionysus returned to the city of his birth,

but his cousin, Pentheus King of Thebes, refused to believe he was a deity and son of his

aunt Semele. After mocking Dionysus and attempting several times to imprison him, he

finally incurred Dionysus’ anger. Pentheus’ mother Agave and other Theban women

became Maenads under Dionysus’ spell and roamed the forest as crazed wild women. When

Pentheus pursued them, the Maenads thinking he was a mountain lion, rushed in and tore him

limb from limb. When Dionysus restored their sanity, the sobered Agave discovered she had

dismembered her own son. These tales illustrated that the dual nature of Dionysus was

characteristic of wine – it could be both beneficial and detrimental.

V. The Bacchanal Retinue

Dionysus traveled with a very unique entourage of Bacchanalia creatures and associates

– quite a cast of characters.

Silenus - the oldest of Satyrs was Dionysus’ debauched mentor and

most frequent companion. He was usually depicted as bearded, drunken, sometimes with

either goat or horse ears, hooves and tail. Although prophesy was attributed to him, most

often he was perpetually stupefied with wine, unable to distinguish truth from falsehood.

Pan – was a pastoral deity who made flocks fertile so appropriately

he had horns, legs and ears of a goat. Although he was physically unattractive, he had

amorous tendency to seduce nymphs. He could be mischievous and sometimes ill tempered

often frightening unwary forest travelers. He was known for playing his reed pan flute and

for blowing into a conch shell. When he blew the conch shell the sound emitted created so

much anxiety and agitation that our word panic is derived from Pan.

A surprising reference to Pan was told by Spanish writer, Rodrigo Caros in a book in 1634.

In his history of Seville he described how Bacchus founded Cadiz and ruled until his

companion, Pan, took over as regent. The region therefore became known as Pania

which later became Hispania. It was said that Philip IV considered himself as a

successor to Bacchus.

Maenads or Bacchantes – were the most fearsome in the bacchanal

retinue. They were mortal wild- haired women followers who roamed mountains and forests

adorned in ivy and animal skins waving the thyrsos (reed tipped with pine cone). While

under Dionysus’ influence, they danced and worked into an ecstatic frenzy capable of

tearing apart animals with their bare hands - definitely someone to avoid meeting on such

an occasion.

Satyrs, Sileni, fauns, centaurs – were forest participants in the

Bacchanal. Satyrs were sensuous creatures usually part man part goat

(hooves, horns, ears, tail) who danced, played music and certainly knew how to party.

Ancient Greek and Romans depicted them as ugly with beards, snub noses and bulging

foreheads. Sileni were similar to satyrs, but were older and often had

either horse or goat legs horns, ears, and tail. Fauns were gentler,

handsome young males with discrete horns and goat ears, tail and usually human legs. They

were the most attractive of the group and popular in sculpture. Centaurs

sometimes in Bacchanalia were creatures with the head and torso of a man and body of a

horse and were sexually aggressive.

Nymphs – were beautiful maiden-creatures who in habited, the sea,

rivers, woods, trees, meadows and mountains as followers of various deities. In

Bacchanalia they were sensual, scantily clad or nude usually “partying” with

satyrs and fauns.

Putti – boy- babies were used as an art form to display by their

actions life forces, emotions, sensations - the spirit expressed in a scene. They were

frequently part of a Bacchanal, usually very busy and active. A putto sometimes hid behind

an ugly mask of Silenus playing boogeyman trying to scare other putti. Such a putto is a

called a Larvate and represented empty fright, silly unfounded fears or tension

caused by a disguised putto trying pretend to be fearsome. Other charming, devotional

putti dutifully tend grape vines and make wine. Satyr-putti cavort in

wild abandon, playing instruments, dancing and often drinking in excess displaying the

physical effects of wine illustrating its mental alteration.

Dionysus – in his earliest rendering in Greece was a bearded

Zeus-like figure, but soon evolved into an attractive long-haired Apollo-like man. In

Euripides’ tragedy Bacchae, the story of Pentheus, Dionysus was described as

“foreign and woman-like.” Over the centuries artists’ renditions have been

varied: an infant, handsome lover of Ariadne, effeminate and even fat full

of the good life. He usually appeared good-natured, perhaps grinning and enjoying the

celebration. In ancient times he was shown offering wine, but never drinking it. His head

was crowned with ivy (immortal symbol) or grape leaves and often wore leopard or lion

skins.

VI. Bacchanalia Iconography

Besides his unusual retinue, Bacchus had special attributes and symbols.

The Dithyramb was poetry in choral song and dance praising Dionysus and

essential in the ritual. Maenads sang and danced and satyrs played musical instruments

(tambourine, pipes, clappers) thereby enhancing the intoxication of the wine. Loud

music provided passion in the reverie and created the spirit of wild abandon.

The thyrsos was the iconic fertility symbol of the Cult of Dionysus

heralding the Bacchic celebration. It was carried by either Bacchus or Maenads. The

thyrsos was a staff tipped with a pine cone and sometimes wrapped in ivy or grape leaves.

Goats were Dionysus’ sacrificial animal. They are present in most

bacchanal scenes usually being restrained by the horns or ridden by satyr-putti trying to

protect the tender grape leaves from being eaten. Roman poet, Virgil said, “Beware of

the rough-toothed goat.” Goat skins were used to hold wine.

Snakes sometimes in Bacchic celebrations were possibly from Minoan

tradition as symbols of rebirth and rejuvenation because snakes shed their skins. In

ancient periods in this context they were not symbols of evil.

Masks relevant to Greek theater were important attributes of Dionysus.

(see History…).

Leopard skins were worn by Dionysus and he traveled by chariot pulled by

lions. Wild cats with their capricious behavior symbolized Dionysus’ irrational wild

nature. Hunt animals as dogs referred to the story of Dionysus driving lions from Mt.

Nysa.

VII. History of the Cult of Dionysus and Bacchanal

The origin of the Cult of Dionysus is unknown. Fertility worship was prevalent in early

Bronze Age Mediterranean area. Scholars postulate that some Bacchic elements may have

their source in cultures of Asia Minor (Phrygian, Lydian) and in the Minoan civilization

of Crete. It has been substantiated that by 1250 BCE, Dionysus was accepted as a god and

rituals were part of Mycenaean religion.

However, Dionysus achieved greatest prominence in Classical Greece and festivals and

bacchanals were ubiquitous throughout the Greek World. In 500 – 400 BCE, the Great

Dionysia was the foremost celebration of civic pride in Athens and was so important that

the entire population was encouraged to attend including women, who in Greek society were

usually cloistered in their homes. The Great Dionysia was a competition between

poet-playwrights creating the great tragedies Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. Greek

theater began with the Dithyramb, poetry of praise sung by a chorus that evolved into

character speaking parts. The competitive prize was a sacrificial goat. The word tragedy

in Greek meant “goat song.” It is ironic that today Bacchanalia has a

connotation of orgy and immorality, but for Athenians it was an important venue for civic

lessons in morality. Aristotle pointed out that its ritual function was to purge

spectators of their emotions of pity and fear through their vicarious participation in the

drama. It is interesting that Dionysus, not Apollo, was the inspiration for Greek Drama.

Apollo represented the rational and civilized side of man’s nature. Dionysus was the

embodiment of man’s irrational, passionate side that unleashed the creative spirit.

He suffered greatly when the vine was pruned just as the tragic hero/heroine suffers

trying to overcome obstacles in their moral struggles.

In the Roman Era the Dionysian Cult may have arrived in Italy through southern Etruria

between 400 – 200 BCE. Roman writer, Livy, in his history of Rome (29BCE) related

that the Senate in the Roman Republic in 186 BCE banned the bacchanal because of

immorality. This led to persecution of the Bacchoi (members) which forced the Cult to go

underground, later to reemerge even stronger. Most scholars believe the charges leveled

against them were mostly false or exaggerated. The unsanctioned Cult had been gaining in

popularity especially among the underclass of society and was considered suspect by the

Senate because it wasn’t under their complete control. This was a period after the

Second Punic War when ethnic fear could be evoked of anything “foreign.” The

ancient Italic deity of fertility and agriculture was Liber Pater. Liberalia was an

ancient festival which celebrated young men’s “rite of passage” by removing

their bulla (lucky charm) and exchanging their toga of childhood for the white toga of

adulthood. Gradually in Latium, Liber became assimilated with Bacchus. In the early

Christian Era, Eastern Roman Emperor, Theodosius II (401 – 450CE) by law ended the

bacchanal and all Dionysian worship

VIII. Bacchanalia Celebration in Greco- Roman World – “Wine, Women and

Song”

The actual ritual practice of the bacchanal in the Greco-Roman world varied by region and

cannot be described with singular complete certainty because the mysteries were not

written down and were known only to the Bacchoi. However some Bacchic characteristics were

known and universal. It was celebrated at night, outside in a wooded location lit by

torches and led by Bacchantes (priestesses) and Bacchants (priests). The thyrsos (reed and

pine cone) was carried by the celebrants. Women were essential

members of the Bacchoi in the role of Maenads or Bacchantes. Sometimes they practiced

animal sacrifice but it is doubtful Maenads tore animals apart in wild frenzy. Music was

another necessary element of the rite and it was used in the

dithyramb praises of Dionysus in song and dance. Loud rhythmic

sounds intensified the euphoria. Wine liberally drunk gave Bacchoi

the exultant power of feeling divine. Wine meant that the god was not only outside them,

but when consumed he was within them too. Sexual involvement may have been a component of

the activity but it was not a necessary inclusion in

the ceremony. The reverie of “wine, women and song” was important because it

represented Dionysus’ wild spiritual release and freedom. The Bacchanal was practiced

by people of all social classes, but it was especially popular with the disadvantaged

because it didn’t require expensive votives, women could participate and worshippers

did not need a temple.

IX. Theology of Bacchanalia

Worship in the Bacchanal had obvious pleasurable orgy-like aspects, but it was the

Cult’s theology that made Dionysus such an important god in ancient societies.

Dionysus, a fertility deity, was life and rebirth. He was the vine painfully and severely

pruned, left as bare stock to emerge alive again in joyful resurrection. He had rescued

his mother from death. He was assurance that death didn’t end all. He was the

expectation that the soul lived on forever. A poignant reference to this was in a letter

written by the Greek writer, Plutarch, 80 CE, to his wife after news of the death of his

little daughter:

“About that which you have heard, dear heart, that the soul once

departed from the body

vanishes and feels nothing, I know that you give no belief to such assertions because of

those sacred and faithful promises given in the mysteries of Bacchus which we who are

of that religious brotherhood know. We hold it firmly for an undoubted truth that our soul

is incorruptible and immortal. We are to think (of the dead) that they pass into a better

place and a happier condition. Let us behave ourselves accordingly, outwardly ordering

our lives, while within all should be purer, wiser, incorruptible.”

(Mythology, Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes, Edith Hamilton)

X. Biography of Luca Giordano

Luca Giordano was born in Naples in 1634 and died there in 1705. He was the son of the

painter Antonio Giordano (1597-1683). Luca was one of the most celebrated draughtsman and

painter of the Neapolitan baroque whose oeuvre included religious, mythological paintings

and many fresco cycles in palaces and churches. He painted in Naples, Rome, Venice,

Florence and later in Spain. Early in life he was influenced by Ribera and his work in

Naples reflected Neapolitan taste in art. In Rome he studied the work of da Cortona, Preti

and Rubens. He created his own style bringing exuberant color and light into his work.

Rubens’ paintings made a lasting impression on him as shown in the treatment of faces

in his figures. In admiration of him, Giordano painted Rubens Painting an Allegory of

Peace. He was a respected fresco artist and

painted altar pieces in Venice and vaults and a dome in Florence. He painted Bacchanals

and other mythological subjects including A Triumph of Bacchus (untraced) for

Cosimo III de Medici. It was said in Florence he used two styles – baroque in

religious subjects and an elegant classicism in secular decorative work. He was in great

demand as a decorative artist and was called twice by Philip IV of Spain, but both times

he cited pressing affairs at home. When Giordano was sixty years old, Charles II was able

to use leverage to bring him to Spain. His son’s political appointment would only be

renewed if Luca Giordano agreed to paint for Charles II in Spain. His commitment of nearly

ten years in Spain eventually advantaged other family members. He frescoed the many vaults

at the Escorial, scenes in monasteries, churches and the sacristy ceiling of the Toledo

Cathedral. His speed of execution and huge output earned him the nickname “Luca Fa

Presto.” His legendry speed and capacity to improve was amusingly expressed by the

Prior of the Escorial who wrote Charles II the following:

“ Today your Giordano has painted ten, eleven, twelve figures three

times life

size, plus the Powers, Dominions, Angels, Seraphim and Cherubim that go

with them and all the clouds that support them. The two theologians he has

at his side to instruct him in the mysteries are less ready with their answers

than he is with his questions, for their tongues are too slow for the speed of

his brush. (Grove, Dictionary of Art).

After his death he was considered a versatile painter who imitated other

styles. However, Francesco Solimena, his pupil-friend, understood and appreciated

Giordano’s creativity and absorbed his painting style.

XI. Other Bacchic Art in the Ringling Museum

The Ringling Museum has other Bacchic works of art. Portrait of a young Aristocrat,

SN 380, by Jean-Marc Nattier (1730) in Gallery 15 is an amusing depiction of a chubby male

aristocrat playing the court role of Bacchus. In his right hand he holds a Thyrsos and in

the left a cup of wine. He is draped in leopard skin with a live leopard by his side.

Many Ringling Chiurazzi “cast bronzes” are part of “the cast of

Characters” in Bacchanalia. The Elder and Younger Furietti Centaurs (from

Hadrian’s Villa) greet you at the entrance of the Art Building. Four others are

placed tantalizingly on the loggia. The Satyr with Young Bacchus, Drunken

Faun and Sleeping Faun reside on the North Loggia. Dionysus with Grapes and Goat,

known as “Rosso Antico” in the book, Taste and the Antique, is standing

in the beginning of the South Loggia.

XII. Background on Ringling Museum’s A Bacchanal by Luca Giordano

“A Bacchanal Fete” SN 161 was purchased by John Ringling as a Luca

Giordano painting in December 1929 from the Collection of Jean Desvignes, Paris, sold at

the American Art Association NYC. Suida in 1949 designated it as one of six

Giordano’s (SN 156,157, 158, 159 160, 161) and Susannah and the Elders SN

162 as “Studio of Giordano” although originally attributed to Titian. Tomory in

1976 referred to “A Bacchanal” SN 161 and Susannah and the Elders

SN 162 as a copies “after Giordano.” He agreed with four of Suida’s

Giordano’s, but Jacob and Raphael at the Well SN 158 he attributed to

Francesco Solimena. Tomory stated that A Bacchanal had conservation in 1947-49:

major losses on left side and center on lower left of canvas. It was stated that A

Bacchanal, had elements from both Ribera and Giordano, but was possibly painted by a

studio assistant or an independent Neopolitan.

In the present registrar A Bacchanal is attributed to Luca Giordano. The Ringling

Museum has five paintings by him:

SN 156 Adoration of Shepherds

SN 157 The Flight into Egypt

SN 159 Allegory of Faith and Charity

SN 160 Mars and Venus with Cupid

SN 161 A Bacchanal

Jacob and Rachel at the Well SN 158 is attributed to Francesco Solimena and Susannah

and the Elders SN 162 as “in the style of Giordano.”

Recently Michelle Scalera did a ten month restoration of the Bacchanal painting. It had

water damage in the lower portion during long term storage. She found a J signature mark

on the canvas. Luca Giordano sometimes signed his works as “Jordanus.”

XIII. Discussion of A Bacchanal, by Luca Giordano

Luca Giordano’s painting has many traditional bacchic features and is infused with

humor. Its composition has curious contrasting aspects. In the central area of the canvas,

gentle Nymphs of Nysia serenely recline in classical poise observing young Bacchus’

misbehavior. Infant Bacchus, raised onto the shoulder of a satyr, is pouring a cup of wine

onto the head of a satyr-putti below him. It is reminiscent of a toddler sitting in a high

chair overturning a cup of milk just to watch the liquid pouring out. The calm Nymphs

don’t seem very upset by his naughty behavior, although they may be whispering to

each other,” Look at what he is doing now.”

Their placidity is in contrast to the wild activity all around them. Satyr-putti are

obviously very inebriated and their grotesque faces are distorted in sloppy drunken

expressions with wine oozing from their mouths. Silenus may be a bearded sleeping figure

in the background and a similar figure appears in bacchanals by other artists. Other

satyr-putti are handling the goats,

holding them back by their horns and riding them. Musical instruments are played by

dancing satyr-putti creating the all important Bacchic din. A little pan-putti in the

center lower edge, is blowing a conch shell. This is in reference to Pan’s panic,

but in this situation the shell blown by a little putti is a lesser panic or disturbance.

This symbolizes frenetic spirit in the scene. Dogs appear among the throngs as Bacchic

symbols of hunting and wild nature. The foliage is thick and darker than in an idyllic

pastoral scene. All this wild nosy “rave” below is contrasted by gossamer-winged

putti fluttering above faithfully tending the grapes.

XIV. Bacchic Theme by Other Artists

Luca Giordano and many of the great artists of the 1400s – 1700s had their own

creative expressions of the Bacchic theme. Therefore paintings, engravings and sculptures

of this subject were represented in so many different ways. Michelangelo sculpted both a

young Bacchus and a drunken Bacchus and drew a Children’s Bacchanal.

Titian’s The Andrians - Bacchanal) (fig.1) and Bacchus and Ariadne

(fig.2) painted for Alfonso d’ Este were described as joyful having delicacy and good

taste.

Later The Andrians was acquired by Philip IV. Very

different is Diego Velazquez’s painting The Triumph of Bacchus (fig.3), a

scene with drunken Spanish peasants. Others referred to it as “The Triumph of Bacchus

in burlesque” and later it was known as “The Topers.” This painting was

commissioned by Philip IV and it demonstrates, as with the Titian, his interest in the

subject. P.P. Rubens created The Bacchanal (fig.4) with a very unflattering image

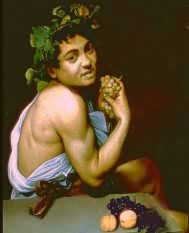

of the debauched Silenus and his consorts. Caravaggio’s Bacchus, 1596-97

(fig.5) and his Self-Portrait as Bacchus, 1593-94 (fig.6) couldn’t be

more different. His later Bacchus is exotic, Japanese-looking, white, soft and

effeminate. His Self-Portrait is unclean, sickly perhaps indicative of the

influence wine had in his personal life contributing to his propensity for getting into

trouble. Luca Giordano and many other artists give us pleasure with their unique

interpretations Bacchanalia.

ringlingdocents.org

|