|

|

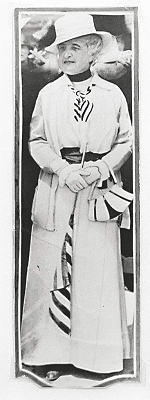

A century ago, Bertha Palmer changed the region

By Harold Bubil. Sarasota Herald Tribune. Published: Sunday, January 17, 2010

She dined with kings and dressed like royalty. She took the $8 million her late husband

left her and turned it into $20 million. She had the confidence and bearing to transform

wilderness into farms, and convince hard-bitten cattlemen to change their ways.

An in-law of a president (U.S. Grant) and a prince (Russia's Prince Cantacuzene), she

wasn't above walking the fields with her hired hands, speaking to them as if equals.

She was Bertha Palmer, and 100 years ago, she changed Sarasota, an event celebrated in the

“Year of Bertha Palmer.”

"At the end of this year, there shouldn't be anyone in Sarasota who doesn't know who

Bertha Palmer was," said Hans Johnsson, initiator and leader of the yearlong,

countywide celebration, which continues Thursday with "An Afternoon Tea With Bertha

Palmer" at Myakka River State Park, and Jan. 31 with History Day in the Park at

Phillippi Estate Park.

About 50 events are planned (www. BerthaPalmerAlive.com). It has been a big undertaking,

with a number of groups lending support or participating, including the Historical Society

of Sarasota County; Historic Spanish Point, which has told the Palmer story for decades;

and the Sarasota county and city commissions.

Hope Black, who chose Bertha Palmer as the subject of her master's thesis in the Florida

Studies program at USF-St. Petersburg, is the project's history adviser. |

Johnsson, a board member of the Historical Society of Sarasota County, isn't sure

exactly how he came up with the idea. When he and his wife bought a house in the

Stoneybrook subdivision of Palmer Ranch, he researched how the ranch got its name.

"I found that this woman was absolutely exciting," he said. "The things she

did were unheard of. The significance she had for the development, especially in southern

Sarasota, was absolutely unique: her cattle ranching, and her new initiatives in citrus

marketing, using her network in Europe and the U.S. She knew people all over" who

could promote Florida fruit.

Students of Palmer say she was at least as important a figure in early Sarasota history as

John and Charles Ringling and developer Owen Burns.

"She brought all sorts of new ideas," Johnsson said. "Her lifestyle was new

to people in Sarasota, a small farming village. Here was a woman decision-maker. All the

other pioneers had been men. All those who made the decisions were men. And then, all of a

sudden, here was a woman who made big decisions, and took responsibility for them. With

her fortune, she had some money to play with on the table, so when she had big ideas, she

had the power to execute them."

One of those ideas was to buy up to 80,000 acres, or about a quarter of the land in what

was to become, in 1921, Sarasota County. She also bought in Hillsborough County, owning

140,000 Florida acres at one time.

Potter Palmer, her husband, built a fortune in real estate and retailing. "Potter had

urged her, for many years, that if something should happen to him, that she should invest

in real estate," said Black. "Property, property, property."

That's exactly what Potter Palmer did after he retired from the dry goods business in

1865. Having made a fortune by stockpiling cotton in advance of the Civil War, and then

selling it in northern markets at high prices during the war, he turned to real estate. He

is credited with turning Chicago's State Street from an alley to "that great

street."

In early evening conversations with her husband, "Cissie" Palmer learned about

business and land investment. She did not forget those lessons when she got to Sarasota.

She experimented with farming, and bought three ranches for the raising of prize

livestock. Two thousand acres of her Meadow Sweet Pastures Ranch was donated by her sons,

Honore and Potter Jr., in the mid-1930s to become Myakka River State Park.

She believed the best way to fight tick-borne diseases in cattle was to dip the animals in

insecticide.

"They told her she was crazy; that it would split the hide of the cattle," said

Black. "She went ahead and did it anyway. She also fenced in her cattle ranges, and

that made them very, very angry. Her land was attacked by some vigilantes who resented

this woman from a rich city coming in and trying to tell these good old boys how to take

care of cattle."

Ahead of her time? Not until 1949 did Florida require fencing of pastures.

Palmer at one time employed 300 estate, farm and ranch workers, and paid the highest wages

in the region, boosting the Sarasota-Osprey economy. But a shortage of local labor forced

her to bring in workers of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, according to a 1960

biography, "Silhouette in Diamonds: The Life of Mrs. Potter Palmer," by Ishbel

Ross. Some locals were outraged. She complained in a 1914 letter, postmarked Paris,

France, to Osprey store owner V.A. Saunders that she would no longer tolerate attacks on

her interests.

"Since buying at Osprey," she wrote, "I have been greatly annoyed by the

annual criminal assaults on my place and on my innocent, unprotected, sleeping Negroes, by

cowardly bands of armed men who came at night to shoot them up and drive them away."

Florida dreaming

It was Jan. 23, 1910, and Bertha Palmer had been a widow for eight years. On a dreary

winter day, while reading the Chicago Sunday Tribune, she noticed an advertisement

promoting a small town in Florida as a subtropical paradise, as Karl Grismer writes in his

1946 book "The Story of Sarasota."

The ad, placed by real estate broker J.H. Lord and city father A.B. Edwards, painted

Sarasota as a new and modern city surrounded by the "richest land in the world."

Prescient investors would prosper.

The advertisement did not mention that Sarasota, then truly a "sleepy fishing

village," was on the heels of a dramatic real estate recession, one in which one

could buy 80 acres, a house and a barn five miles south of town for $1,020.

Bertha Palmer, then 61, dreaming of warmth and palms, had her father, H.H. Honor , with

whom she was very close, call on Lord to find out more. Soon the great lady was planning a

visit to Sarasota, to be accompanied by her father, brother and two sons, Honore and

Potter Jr.

Sarasota, which then had 900 residents (and no electric service), was excited that such a

woman was coming to visit. It was also mortified. Surely, they feared, she would not be

happy in the Belle Haven Inn, which had gone shabby. So a portion of the new Halton

medical facility was readied as suitable quarters.

Once she arrived, though, and commented that the isolated and impoverished town was

"refreshingly quaint," Sarasotans realized they had worried for nothing. Bertha

Palmer was as comfortable with common people as with kings.

"A swell girl," her ranch manager, Albert Blackburn, called her in

"Silhouette in Diamonds." Although her friends were baffled by her sudden

interest in wilderness farming, wrote Ross, Palmer had had enough of the social whirlwind

of her life until then. In Sarasota, she found real people, not pretenders or royalty.

"Bertha was as adept in the wilds as in a Victorian drawing room," wrote Ross.

She found "refreshment in fundamental things."

From those fundamental things, she built a real estate and agricultural empire, and

brought attention to the area that attracted her wealthy Chicago friends. "Thanks to

her influence, Sarasota pushed ahead as a popular resort," wrote Ross.

It also prompted the city to modernize by installing seawalls, a power plant and a

waterworks, and prime the region for the 1920s real estate boom and bust, which Palmer,

for better or worse, did not live to see. After just eight years on the Gulf Coast, she

died of breast cancer.

In Sarasota's history, she is rivaled only by John Ringling as a leading figure, said

Linda Mansperger of Historic Spanish Point in Osprey. It makes up 30 acres of the 300 that

Bertha Palmer's estate, Osprey Point, once occupied.

"They both were so influential in our history."

ringlingdocents.org

|