The Putto - Angels in Art

by Lin Vertefeuille, 2005

Introduction

Putti proliferate in popular culture: on buildings, in decorative arts, on greeting cards

- a popular purveyor of love. But in Art through the ages, the putto has been a curious

little figure, often reflecting philosophy, theology and literature of the time. The putto

in Renaissance art was a winged or wingless, male child figure. The word putto

(plural putti) in Italian vernacular was derived from Latin putus,

meaning "boy." Putti were secular, sometimes profane and definitely not part of

the nine choirs of angels. However, in the Baroque period of art, the putto was often used

in a religious context and the distinction between being secular and ecclesiastic became

less defined.

Beginning of the Putto- Greek, Roman

The conception of the putto reaches back in art to the ancient classical world, where

winged infants were physical manifestations of invisible essences or spirits called genius,

genii, that were believed to influence human lives. Love putti (erote)

were familiars of Eros and Venus. In Bacchanals, which were celebrations of Dionysius

(Bacchus), putti represented fertility, abundance, the spirit of the fruit of life and

were often depicted in wild revelry. Most intriguing was the ancient creation of the larvate-putto

(to be explained later.)

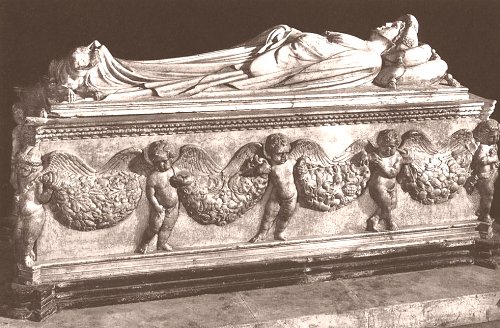

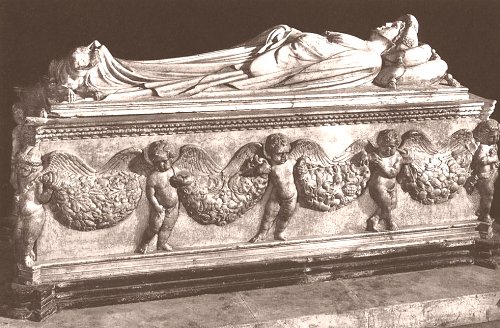

Winged infants were found flying across Etruscan pottery holding garlands of fruit. In the

Roman era carved stone garland swags of leaves, fruit, and flowers [Latin: festa

corona] supported by young male children were important ornamentation and festoons on

buildings and sarcophagi.

Creation of the Putto- Renaissance

During the Middle Ages putti disappeared .... and then reappeared in early Renaissance

Italy. During the Quattrocento, Italians had great interest in their Roman heritage and it

became popular to use two kinds of architectural ornamentation called reggifestone

and reggistemma to adorn churches, funerary objects and public buildings. Reggifestone

was reminiscent of the Roman style of garlands held by putti. One of the earliest

Renaissance examples of this form was the Tomb of Ilaria (1406) by Jacopo della Quercia.

It was described as celebrating Ilaria's beauty and life, not her death, and was decorated

in garlands held by "ingenuous children"

In the reggistemma architectual style of ornamentation, there were usually two

flying putti flaming and flanking either a shield, coat of arms or scroll with text. An

example of reggistemma is on the upper walls of Ringling Galleries 1 and 2.

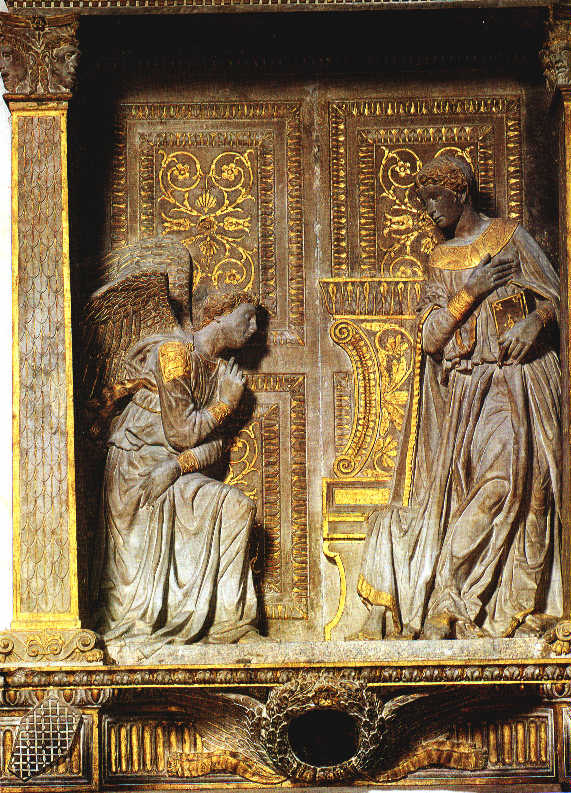

Donatello has been called the real inventor of the putto. This is because he

gave the putto dynamic personality, character and spirited animation. Most significantly,

he integrated the putto into the context of his sculpture and made the delightful little

figure a participant in his work of art. In this way he expanded the putto beyond mere

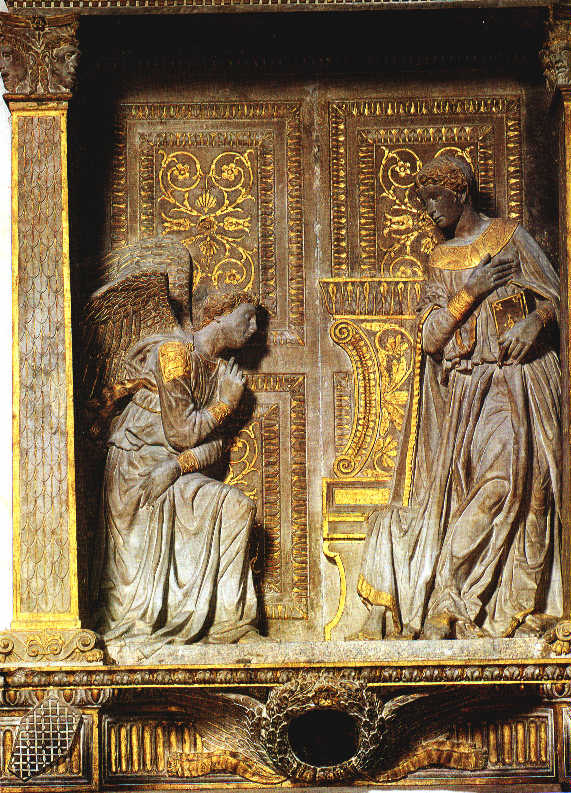

ornamentation and static embellishment. In Donatello's Cavalcanti Annunciation in

Santa Croce, Florence, the Virgin is shown mastering her fear after being first startled

and then recoiling from Gabriel's announcement.

Her surprise and sudden rush of fright the moment before, is reflected in the behavior

of the putti on the frame above her. They mischievously push each other to the shelfs edge

and in childish fright, a putto crouches behind the another peering out hesitantly.

In written contracts of his works, Donatello, referred to his delightful chubby putti as

"spiritelli." This term was particularly descriptive because it was the

diminutive of "spirito - spiritus" which translated from the Greek

"pneuma" meant a spirit, a movement of air and even the act of breathing. Spirit

was the breath of life animating the human organism and departing from it at death. It was

believed that invisible spirits drawn from air were mixed with blood in veins and

arteries. Blood transmitted sustenance and sensations that entered involuntarily through

sensory organs. There were three main types of spiriti: (1 .) natural spirits in the liver

expanded through the body providing nutrition of life - supported by essences in water,

meat and fruits of the earth (2.) vital spirits resided in the heart attended by pulse and

respiration (3.) animal spirits were the most rarefied and located in the brain, rushing

through nerves connected to sense organs where they receive external influences

communicated by spiriti sensitivi. The spiriti sensitivi were many, varied, and caused

random impulses, and emotions such as: surprise, sudden erotic arousal, panicky

disturbances, drunken giddiness, wonderment, joy... This is where we get that

expression," as the spirit moves." The putto-spiritello was the physical

representation in art of these invisible spirits that evoke emotion and thought in all of

us.

Love - Putto

In scenes with Venus, Eros (Cupid) and nymphs erote-putti were spirits of love. Sometimes

they represented gentle subtleties such as catching someone's eye, or why we are attracted

to a certain someone and other times they represented strong passion. A less familiar

aspect to us is the erote ceremonial procession popular in the Renaissance Florence.

Lorenzo de' Medici celebrated love in a Triumph of Love procession. A triumphal car

(trionfo) decorated in gold, silver and jewels had Eros featured in the center with erote

on each comer holding flaming torches. Young men and women as lovers walked beside the

trionfo surrounded by music and merrymaking. This kind of procession related to feudal

rituals rooted in chivalry and courtly love. Sometimes these processions were more subdued

and celebrated the triumph of chastity.

In Counter-reformation art, erote were allegorical representations of God's love, our love

of God and the Church. In the 18th and 19th centuries romantic images of love were popular

and the endearing erote became quite sentimentalized. Today the putto is often referred to

as a cherub. This is not to be confused with the Cherubim~ which are one of the Choirs of

Angels. The putto is neither angel or Cupid. However, they were frequently combined with

angels or used in the context of angels in art of the Baroque period.

Bacchanal - Putto

|

|

Another

popular application of the putto was in the bacchanal. In Donatello's Judith and

Holofernes (left), putti cavort and act out the effects of inebriation- loss of

judgment and narcotic sleep that overwhelmed General Holofernes and brought him to his

shameful end (closeup above). |

|

Putti celebrating revelry in honor of Dionysus reinforced

the dangers of such excesses. Larvate putti and satyrisci (small satyrs) were the spirit

of wild abandon (orgy) and (larval) hallucinations. Bacchanal scenes celebrated

fertility and abundance and hard working putti tended the vine representing the natural

spiriti that give us sustenance. Today we still refer to alcohol as "spirits." |

In Christian art the bacchanal had quite a different meaning. Wine became the symbol of

God's blood and sacrifice. In a parable Christ said,"I am the Vine" and early

church fathers referred to "the grape trampled for our salvation. The putto was the

natural spirit (pneuma) animating from the vine as a nourishing substance. Putti tending

the vine were nurturing our faith. Sometimes bacchanals depicted infant putti attacking or

riding a goat. This theme came from Virgil's reference to new shoots and leaves as

"the tender child" who must be protected from the sharp-toothed goat.

The Bacchanal painting by Luca Giordano in Gallery 8 is a wonderful example of

Bacchanal putti. Visitors often misinterpret the wine for blood in this orgy. This is

certainly not a representation of Christ's blood.

Larvate - Putto

The larvate was an enigmatic spiritello. This putto was shown in mischievous antics

playing bogeyman, scaring companions by wearing the Silenus mask and often playing with

Mars's helmet or shield. The putto behind the mask was called a larvate

|

|

The mask was the ugly face of Silenus, who was the hairy debauched satyr companion of

Bacchus. The larvate represented empty fright - those frights we feel that are unfounded

and without real cause. They are involuntary conflicts and desires that prey on the human

heart. Ralph Waldo Emerson referred to these frights as "hobgoblins of little

minds." They could be serious as our fear of death or lesser childish ones- the point

was they were frights that haunt us but we can do nothing about them. Also our' fears may

be greater than the reality of what we fear. A great description of the larvate is,

"The mask pretends to cover something tremendous and terrifying, but which is really

nothing" - just a little putto playing pranks. When the larvate was used in love,

bacchanal or dream scenes, he created tension, possibly anxiety and sexual arousal.

Interestingly, the word larvate is used today as a medical term for a disease that is

masked. |

Dream - Putto

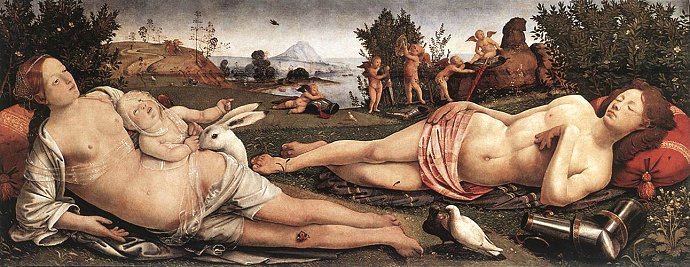

When putti were shown playing in the background or around a recumbent figure, it indicated

a dream sequence. Putti were the feelings and emotions the reclining figure was

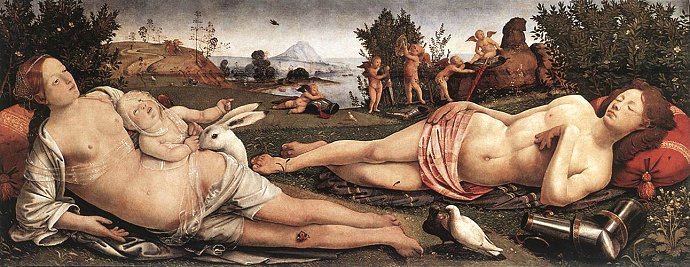

experiencing in the dream. A dream was illustrated in the painting, Mars and Venus

by Piero di Cosimo (below) and it is so different from The Building of a Palace

in Gallery 4. It is Mars' dream and erote playing in the background with his discarded

armor show he has let down his guard. This suggests that Venus has completely seduced him

and love conquers war. This painting was owned by Giorgio Vasari, the Renaissance painter

and author of Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Architects, Painters and Sculptors.

Panisci - Putto

Putti called panisci were associates of the woodland god, Pan. In mythology, Pan with goat

hoofed feet and pan flute was believed to blow a conch shell horn that evoked extreme

panic enough to terrorize the Gods and overwhelm armies. In fact the word panic is derived

from Pan. Putti in art were shown in mischievous play blowing a conch shell. These"

little pans" when they blew a conch shell, they created little panics, that were

sudden panicky distractions that confuse the mind diverting it from serious business.

Mars and Venus (below), by Sandro Botticelli, is an musing example of panisci

used in Mars' dream. You can certainly tell the pattisci are up to no good by their

malevolent facial expressions. A pancisci blowing the conch shell is causing Mars' sexual

panic-arousal The other panisci are holding Mars' lance, his phallic symbol The swirled

shape of the conch shell symbolizes woman-Venus. The panisci are thrusting Mars' lance

into Venus' conch shell. This is putti portrayed erotica!

Water Sprites - Putto

Charming putto are often found in fountains holding a dolphin. These water sprites

represented the natural spirit or essence of the water and its life giving force.

Musical - Putto

To end on a high note, delightful musical putti are particularly charming as they dance,

play instruments and sing. The musical putto was the spirit of music whose rhythms and

melodies, when heard quickened the heartbeat and stirred the soul. They were exuberance

expressed by the sounds and joy felt by the listener. Donatello's frieze in the Cantoria

(Singing Gallery) in the Florence Cathedral was described in the Dictionary of Art,

"...conveys the ecstatic dance of souls of the innocent in Paradise."

Conclusion

In conclusion, the putto in the 1400's - 1600's was a personification of human spirit and

emotion expressed in art and was much more than just an endearing sentimental symbol of

love.

The Ringling Collection does not have a diverse representation of putti. Love-putti are

predominant in our paintings. They are in religious allegories and in mythological

contexts.

Putti are decorative architectural elements found in the Museum's door surrounds and are

quite prominent on the fireplace and on the wall cornice Gallery 21 (see photo below).

Reggistemma (a shield flanked by two putti) is displayed just below the clerestory in

Galleries 1 and 2.

Peter Paul Rubens effectively used reggifestone in three of our Eucharist paintings: The

Four Evangelists, The Meeting of Abraham and Melchizedek and The

Defenders of the Eucharist. Putti with garlands of fruit are in the act of

decoratively hanging the tapestries, cleverly creating the illusion of a tapestry within a

tapestry.

Sources:

Dempsey, Charles. Inventing the Renaissance Putto. University of North Carolina

Press, Chapel Hill and London, 2001

Duston, Allen and Nesselrath, Arnold. Angels frorn the Vatican. Art Services

International, Alexandria Virginia, distributed by Harry Abrams, Inc.,44 - 60. 1998

Hall, James. Dictionary of Subjects & Symbols in Art. Westview Press,

Boulder, Colorado, 1979

Dictionary of Art, Macmillan Publishers Limited, London 1996

ringlingdocents.org

|