Burns and Ringling locked horns over Ritz

By JEFF LAHURD

Nothing so announces to the rarefied world of first-class travelers that a city has

achieved top-drawer status than the construction of a Ritz-Carlton hotel.

Many trace Sarasota's most recent land boom and downtown resurgence to the Ritz-Carlton,

which opened with fanfare at the end of November 2001 and went on to become one of the

top-rated hotels in the chain.

The project, which was put together by business associates-turned-courtroom brawlers Kevin

Daves and C. Robert Buford, recalls a similar scenario that played out in the local press

nearly 80 years ago.

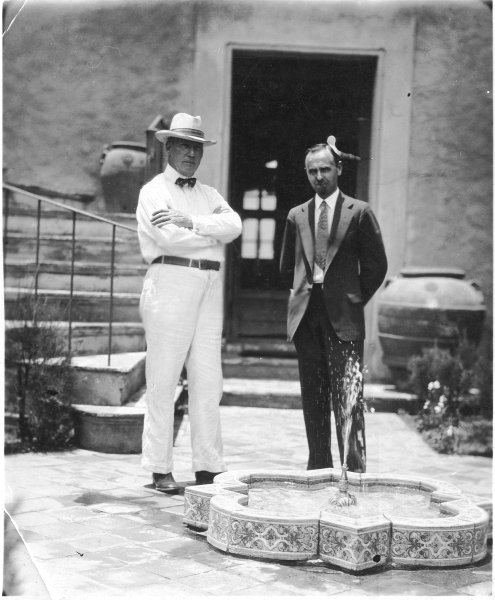

It occurred at the tail end of the Roaring '20s boom and concerned a Sarasota Ritz-Carlton

Hotel and two associates turned bitter adversaries, businessman Owen Burns, the area's

first major developer, and circus man John Ringling, art collector, railway man, banker

and developer.

This duo had participated in many local projects together. As Ringling was away from

Sarasota on business a great deal of the time, Burns became his point man, a hands-on

supervisor who could be trusted to get the jobs finished.

It was Burns' construction company that built the Ringling mansion, C d'Zan, and the

first Ringling Causeway, and purchased for Ringling much of the property that would make

up his projects on Lido, Longboat and St. Armands keys. Burns' dredging company scooped

and filled Golden Gate Point as the starting place for the Ringling bridge and worked in

and around the various keys, for which Ringling had grandiose plans.

Burns also had his own major projects under way, and they were many: the Burns Court

bungalows, Washington Park subdivision, the building at Herald Square, the Belle Haven

Apartments, the Burns office building and the grand El Vernona Hotel, the most significant

hotel in Sarasota up to that time and for many years thereafter.

Burns also was the vice president and minor shareholder of Ringling Estates. Ringling was

the president. Both men had high hopes for Sarasota, which had recently been discovered as

a fashionable destination for wealthy snowbirds.

Initially, Ringling had balked about constructing a hotel. At the beginning of the '20s

boom, Burns tried to persuade him to garner concessions from the city and undertake a

first-class hotel project downtown. Ringling demurred, and shortly thereafter, Andrew

McAnsh constructed the Mira Mar Apartments and Hotel on Palm Avenue.

As the real estate market charged forward, Ringling's vision for St. Armands, Lido and

Longboat as a winter nesting place for high-brow tourists crystallized. He determined that

a Ritz-Carlton would ensure his success; it would draw a steady stream of affluent

visitors to his keys.

Burns was already well into his El Vernona Hotel project when Ringling finally decided to

move forward with the Ritz-Carlton.

The timing for both men could not have been worse.

On Sunday morning, March 14, 1926, the Sarasota Herald headline read: "Start work on

Ritz-Carlton Hotel Monday." The article opined that it would be the greatest hostelry

in the state of Florida and was expected to be completed "very soon."

Sarasota, it seemed, had truly arrived -- but in fact, the party was nearly over.

Both Burns and Ringling were at the top of their games in the mid-'20s. The grand El

Vernona, named for Burns' wife, was moving ahead as scheduled, the Ringling Causeway had

been completed, and thousands drove across to view St. Armands, Lido and Longboat keys,

with their wide, palm-lined streets, antique statuary and the hallmark Harding Circle.

Daily concerts were given by the Czecho-Slovakian National Band, brought to town by

Ringling to add excitement to the grand opening of the Ringling Causeway. Priced at $3,000

and up, sales of home sites on Ringling Estates, "America's Lido," were brisk.

But outward appearances belied the fact that by the beginning of 1926, real-estate sales

were slowing throughout Florida. When a hurricane tore through Miami that September with

devastating force, property values began to plummet and newcomers slowed to a trickle.

The Ritz-Carlton project required $800,000 in capital, toward which Ringling put in

$400,000 of his own fortune, and Ralph Caples was charged with raising the balance within

the community.

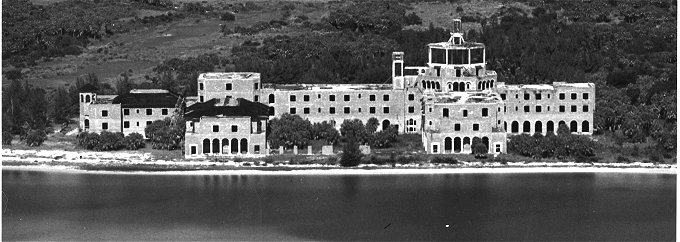

As the five-story luxury hotel began to rise proudly from the south tip of Longboat Key,

money began to dry up, progress slowed and only Ringling's funds kept the project moving

forward.

It was at this juncture that Ringling began dipping into the assets of Ringling Estates,

in which Burns held a 25 percent interest. Burns sought an injunction to prevent Ringling

from "manipulating the Sarasota Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company and the John Ringling

Estates Inc. to require the one to stand for the obligation of the other." Burns saw

his money being frittered away in an ill-advised attempt to fulfill Ringling's promise.

When Burns ceased to be vice president of Ringling's company in 1927, there were nearly $4

million dollars in assets and very little debt. Burns' suit claimed that Ringling was

involved "in a studied scheme to cause John Ringling Estates to underwrite loans to

the (Ritz-Carlton) hotel company," and ultimately confiscate Burns' 25 percent stake.

It would be difficult to find two men more different than Ringling and Burns. Burns was

reticent, a gentleman and loving husband and father. He shunned the spotlight, and his

business dealings were above board. Ringling, on the other hand, was boisterous and

colorful -- a showman. He had no children, and his marriage to Mable was helped along,

according to his nephew Henry North, by "Aunt Mable's loving acquiescence."

Often his business dealings were convoluted and iffy; hiding assets when it suited him,

exaggerating them when necessary.

Burns moved here in 1910 and bought out the holdings of the Florida Mortgage and

Investment Co., and his business interests concerned only Sarasota. Ringling, traveling

throughout the country with the circus, dabbled in numerous far-flung ventures: oil, ranch

land, railroads, a stake in Madison Square Garden. He had homes in New York and New

Jersey.

The two were never close. In letter and telegram exchanges, through which they conducted

much of their business, it was always "Mr. Ringling" and "Mr. Burns,"

never "John" and "Owen." They did not socialize together.

The courtroom drama involving Ringling and Burns came to a head at the end of 1930. By

then, Sarasota had suffered through the real estate bust and, along with the rest of the

nation, was mired in the Great Depression. The optimism of the preceding decade was lost,

and foreclosures replaced grand openings as the order of the day.

In the end the duo reached an accord and Burns' charge of fraud against Ringling was

dismissed. As set forth in the court's final decree: "That neither the defendants,

John Ringling, John Ringling Estates Inc., or the Sarasota Ritz-Carlton Hotel company are

guilty of any ... fraudulent or illegal acts as charged in the bill of complaint."

It was a grave financial blow for Burns, who also suffered the loss of the El Vernona

Hotel, which was sold at auction to the Prudence Company. To heap insult upon injury, it

would be purchased by John Ringling, who changed its name to the John Ringling Hotel.

Interestingly, as the John Ringling Towers, it was demolished by Robert Buford along with

the Burns office building to make way for today's Ritz-Carlton.

Burns set up shop in the former Sarasota Times building across the street from the newly

named John Ringling Hotel and began the Tre-Ripe Citrus Guava Preserving Co. He died at

his home on Aug. 27, 1937. He was 68. According to his daughter, Lillian, he was not

embittered by his experience with Ringling and just moved forward with his life.

Ringling's final years were painful and difficult. Mable died in 1929; he lost control of

the circus, was constantly feuding with family members and former friends, entered into a

marriage that quickly unraveled and embroiled him in an acrimonious divorce, was hounded

by creditors, became gravely ill, and nearly lost C d'Zan, the sale of which was

prevented only by his death a few days before it was to be put up at auction. Ringling

died in New York on Dec. 2, 1936. He was 70.

As for Ringling's nearly completed Ritz-Carlton Hotel, it stood for decades as a forlorn

reminder of the real estate crash and the breakup of a once-productive business

association. It was demolished by the Arvida Corp. in 1964.

In its place stands the Longboat Key Club.

Historian Jeff LaHurd has written numerous books on

Sarasota and Southwest Florida. His latest is "Sarasota, a History," published

by History Press. Contact him at jlahurd@scgov.net.

Source: www.sarasotaheraldtribune.com

November 7, 2006

More Information like the above.