A Kind of Magic

Jan van Eyck has gone down in history as the alchemist who discovered the secret of oil

painting. But, says Jonathan Jones, the real story is more complicated.

Guardian Website.

Tuesday January 1, 2002

The study is a close, low-roofed room with mullioned windows. Light streams in, voices

carry over the canal, potions bubble in flasks, and through a low wooden door is a yard

where paintings are put out to dry.

Artist and alchemist Jan van Eyck pores over a little wooden panel on which he has tried a

new type of painting medium. The painting looks sharp, brilliant. It catches the light

from the window; the colours seem to glow from inside. Van Eyck, so the story goes, has

found not the philosopher's stone dreamed of by alchemists but something that will make

him rich and famous throughout Europe: oil painting.

Jan van Eyck was one of the most influential artists ever, and perhaps the single most

innovative painter in the history of European art. This is something that Bruges, the city

where Van Eyck lived and worked as court painter to Philip the Good of Burgundy, is not

about to forget. Bruges is European capital of culture in 2002, and is paying tribute to

its most famous artistic citizen with an exhibition that will be one of this year's

highlights.

|

|

It is in Van Eyck's early 15th-century paintings that we first see

representation as it was to be practised by Velazquez and Manet. Looking at his

extraordinarily lifelike portraits, such as that of the Arnolfini couple in the National

Gallery, London, it's hard to grasp that we are seeing a medieval world, painted by a

medieval man.

The story of Van Eyck is one of the most mythicised in art history. For centuries it was

told as gospel fact that Van Eyck was the inventor of oil painting, and that he discovered

it because he dabbled in the occult science of alchemy.

The provocative exhibition in Bruges, Jan van Eyck: Early Netherlandish Painting and

Southern Europe, revisits this old and curious story - and claims that it was the Flemish

artist, and not Masaccio or Giovanni Bellini, who was the true hero of Italian renaissance

painting.

The use of oil as a medium to carry pigments is vitally different from earlier methods of

painting. Oils bear colour more effectively than the mixture of glue and egg tempera that

was used by medieval artists. |

Oil has a brightness to it, a transparency that allows light inside the

painting; oil paintings shine. Transparent layers of oil paints - glazes - can be built up

to give a picture depth, a sense of space fundamental to the way in which European

painters constructed illusory worlds between the 15th and 19th centuries.

When we think of the power of the old masters to make the world live on canvas - the

hallucinatory art of Vermeer or Caravaggio - it's oil painting that we picture. And it's

the bewitching power of this medium that gave rise to the legend of Jan van Eyck and his

great discovery.

Artists in 15th-century Italy, where the renaissance began, were obsessed with creating a

deceptive image of the world through single-point perspective - and yet they still used

egg tempera paints with their hard, opaque blocks of colour.

That was why Van Eyck's art looked so magical to them. That was why, it was said, a young

adventurer from Sicily travelled north to sit at the alchemist's knee and learn his

secret.

The story is told by all the early historians of European art: by Giorgio Vasari in his

16th-century Lives of the Painters, and by Dutch art historian Carel van Mander in his

17th-century compendium of the lives of northern artists, The Painter's Treatise.

It's the origin myth of oil painting: Van Eyck discovering the secret in his alchemist's

laboratory before it is gradually carried across Europe, from north to south, until, by

the beginning of the 16th century, oil painting is no longer a secret.

|

|

We can picture Van Eyck's laboratory from renaissance paintings of

alchemists in their lairs, or St Jerome in his study. Van Eyck gave the appearance of a

learned man; he loved to paint words, making puns in trompe l'oeil gothic script on his

frames.

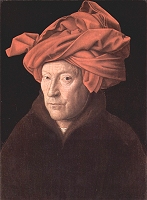

"Als Ich kan" (As I can), says an inscription over his 1434 Portrait of a Man, a

play on "As Eyck can". (The subject wears a red turban; it has been suggested

this is a self-portrait.) So it is not difficult to envisage him, as Vasari does, trying

to crack the riddle that will turn base metal into gold.

He didn't crack it. But his skill at compounding led elsewhere. One day he was enraged to

find that his tempera paintings, drying slowly outdoors, had been cracked by the sun's

rays. Determined to find a way of painting that would dry more quickly, inside the studio,

he tried suspending his powdered pigments in different liquids until he hit on a mixture

of linseed and nut oils. |

Van Eyck was delighted by how quickly it dried, and even more delighted

with its aesthetic effect. He saw that oil paints had a natural "lustre", as

Vasari puts it; he also noticed that he could mix colours far more subtly.

But Van Eyck had no intention of sharing this secret. His paintings still seem to have an

occult quality - historians will never stop debating the meaning of Van Eyck's Arnolfini

Marriage. And yet the real mystery of this very early oil painting, dated 1434, lies in

its space, depth and texture, as if we really are looking through the flat wooden panel

into a mirror universe. The illusion is at once absolute and acknowledged.

Van Eyck reminds us of his skill even as he uses it to fool us; even as we lose ourselves

in the belief that this is a photograph of a late medieval merchant's house, we notice the

flamboyant signature in the middle of the painting, there on the wall. Jan van Eyck was

here. He conjured this apparition.

Van Eyck's secret became notorious, say the chroniclers, and the paintings he made with it

dazzled all who saw them. He passed the formula on to a handful of Flemish followers but

they guarded it closely.

His paintings were contemplated in the courts of Europe as objects of wonder and

curiosity. They smelled differently from other paintings, but no one could work out why -

until a painter from Messina in Sicily saw one of his paintings at the court of King

Alfonso I in Naples.

Antonello da Messina, "a person of good and lively intelligence", had business

in Naples, but was so amazed by Van Eyck's painting that he dropped everything and set out

at once on the hazardous journey, from southern Italy to Flanders, to find Van Eyck. The

Flemish painter was an old man, and flattered. Da Messina became a friend, almost a son to

Van Eyck, who melted and told him everything.

Soon after sharing the secret, Van Eyck died. Da Messina set out for Italy again, but

never got home to Sicily. Instead he stopped in Venice. He had a weakness, it was said,

for licentious living, and Venice, with its courtesans and palaces, was his dream city.

He could afford to stay there because the paintings he made in oils, according to Van

Eyck's recipe, were a sensation. He was unrivalled, in fact, until another artist

befriended him, much as he had befriended Van Eyck, and got him to reveal the secret.

Before long everybody knew.

Stories that explain great historical transformations are as popular today as they were in

the 16th century, but the legend of Van Eyck is, sadly, not true. It was accepted as such

for a long time, until conservationists found much earlier traces of oil painting.

Van Eyck was not alone in his "discovery". Texts dated as early as the 12th

century discuss oils, and the systematic use of oils was developed in the Low Countries in

the early 15th century by several artists - most notably Van Eyck and Robert Campin.

And yet the fact remains that Van Eyck was technically unprecedented - not in using oils,

but in manipulating layered, transparent oil glazes to build up the sense of deep, real

space. This was his innovation, and with it he revealed the power of what is known as

atmospheric perspective - the illusion of a receding atmospheric space in the painting,

achieved by gradually paling out colours towards the horizon.

|

|

Van Eyck promoted the idea of oil painting and demonstrated its

effects deliberately. His pictures are full of self-conscious gimmicks designed to show

what oil painting can do. He invented not a technology but the idea of mimesis in oils.

It was Da Messina who brought Van Eyck's style of oil painting to Italy. Da Messina's

assimilation of Flemish technique was so total that for a long time his St Jerome in His

Study, from about 1475, was thought to be a Netherlandish picture. A romantic might almost

see this as a tribute to Van Eyck, a portrait of the researcher who "discovered"

oil painting, sitting in his study.

Van Eyck's simulacra of the world are like spells against time. Vasari claims that da

Messina was impressed by the toughness of Van Eyck's paintings - they did not decay. Even

today they have a bright, clear look.

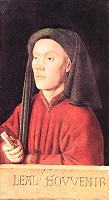

Van Eyck's Portrait of a Young Man (1432) depicts its subject behind a plinth of painted

stone, cracked and worn like a tombstone, inscribed with the words: "L al

souvenir" (Loyal remembrance). Unlike the stone, Van Eyck's painting is pristine. It

has endured almost 600 years. The man whose portrait Van Eyck fixed in oils is still here,

preserved as if by magic. |

ringlingdocents.org

|