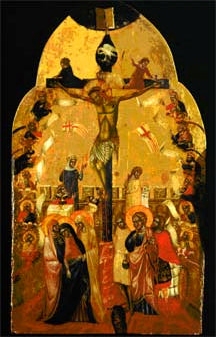

He stirred up strong emotions among his followers and potentially endangered the establishment as well as the Roman empire. According to Christian tradition, Jesus both foretold and allowed his crucifixion, a punishment that was standard procedure in Roman law for political and religious zealots who were non-Roman. The Christian world recognizes this event as the Passion of Christ -- Easter -- a time to reflect on the death and to celebrate the Resurrection of Jesus (a form of "Joshua": Hebrew for "savior"). The Transfiguration and ascent into Heaven that followed his death on the cross declare to the world the truth of his ministry. Accordingly, the crucifixion that followed the Last Supper is one of the principal icons of Christian art, together with the Nativity and Virgin and Child. An early Venetian painting by Marco di Paolo Veneziano in the Ringling Museum of Art depicts the sacrifice: "Christ Crucified by the Virtues," tempera on panel, circa 1340. Veneziano's painting retains earlier Byzantine characteristics: facial types, anatomy and weightlessness as in the central figure of Jesus. It also relates size to sanctity -- the image of Jesus being the largest. In Veneziano's version, Jesus is being nailed to the cross by two figures personifying Obedience and Patience. Charity holds up his head, while Humility stands at the foot of the cross. Allegories of the Virtues, these figures crucify Jesus to prove their devotion to him at his death. The three Marys stand left of the Cross: the swooning Virgin Mary at the center, supported by Mary Magdalene, and Mary, the mother of St. James the Lesser. To the immediate right: Stephaton holds a cane impaling a sponge soaked in wine (personification of the synagogue); in the middle, St. John; and to his right, Longinus (personification of the Church). A chalice and host, symbols of the redemption, rest on the table left of the cross. The pelican, symbol of Jesus' suffering on the cross and the sacrament of the Eucharist, perches above. At the top, the hand of God holds a key and the Holy Book and, at the extreme left and right, Veneziano depicts half figures of 12 prophets. The painting demonstrates genuine religious feeling through expressions, symmetry in composition and in its use of bright, jewel-like colors set upon a ground of gold leaf. Some three decades before the birth of Jesus, the Roman poet Virgil

"anticipated" the essence of this painting in the simple phrase "Omnia

Vincit Amor" -- love conquers all things. This Easter -- today -- the message of self-sacrifice remains as relevant as ever, regardless of one's spiritual convictions. |