|

|

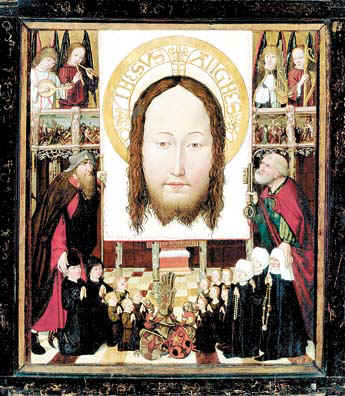

A Family Group Adoring the Veil of Veronica

c. 1490, oil on panel, 31 inches by 27 inches.

By LENNIE BENNETT, St. Pete Times art critic

Published November 6, 2005

Who are these oddly proportioned people?

We don't know. Nor do we know much else about the painting, including the identity of its

creator.

But even without those certainties, this devotional painting, in the permanent collection

of the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, has a story to tell. It pulls us

back more than 500 years, to a time of faith in northern Europe that transcended war,

blight and, as this work demonstrates, death. About its particulars we can only speculate. |

The artist

The painting has been attributed to an anonymous 15th century Austrian called the Master

of the Rottal Panel, which is now in an Austrian museum, because of stylistic similarities

between the two works. Joanna Weber, the Ringling's associate curator,

says this painter, most certainly a man, "was not in the mainstream." Austria

was an artistic backwater compared with Flanders (now part of Belgium), where late Gothic

was yielding to an early Renaissance style.

"Everything about it is more medieval," Weber says, suggesting the artist was

not familiar with Jan van Eyck and Robert Campin's experiments with realism and

perspective in the mid 1400s or with Hans Memling, who would have been his contemporary,

all part of the Flemish school. "But this was somebody with some skill," she

says. "And it has a folk quality that makes it so intriguing."

The details

It's a picture within a picture, containing earthbound elements - a family at prayer, a

church - and heavenly ones - angels, saints and a large head of Christ. A family kneels,

probably in their private chapel. Their coat of arms separates the men and women, who look

dwarfish compared to St. James, holding his pilgrim's staff, and St. Peter, holding the

keys to heaven. They are probably the family's patron saints, not literally present but

there as intercessors between the mortal and spiritual world. The woman on the far right

holds a white cross, which indicates the painting may have been commissioned to

commemorate the death of the family matriarch. Another juxtaposition of the earthly and

heavenly is the carved frieze above the family that depicts the stations of the cross and

then, higher yet, angels playing celestial music from the choir loft.

The Veil of Veronica

The picture within a picture is the large head of Christ on a piece of linen. It's a

representation of the relic known as the Veil of Veronica, and, like many relics, it has

become controversial. The veil was not mentioned in the New Testament, but the apocryphal

Acts of Pilate from the sixth century has an account of a woman drying Christ's face on

the road to Calvary and of the linen being imprinted with his image. The name Veronica is

thought to be a combination of the Greek and Latin "vera icona," meaning real or

authentic icon. A cloth said to be the veil was displayed at the Vatican for several

hundred years, but it disappeared in the 1600s. It showed up later in a monastery near

Rome. Like the Shroud of Turin, it has been largely discredited by scholars, but at the

time of this painting, Veronica's Veil was a venerated artifact.

Symbolism

Of course, the family would not have had the actual veil, and this one, like the angels

and saints, is a symbolic presence. The size of Christ's head, far bigger than that on the

real veil, and the serene features, with no hint of his suffering at Calvary, tell us it

is only an apparition. The inscription on Christ's halo means "the face of

Jesus." Here, Christ is radiant, having conquered sorrow and death. "It's a

visual device," Weber says, "to emphasize the theological point that Christ's

face should be on all of our faces." For the family, it was probably a source of

comfort and a hope that they, too, would someday meet God face to face, surrounded by

protective saints and angels.

Provenance

John Ringling bought A Family Group Adoring the Veil of Veronica in 1929 from his

friend and mentor Julius "Lulu" Bohler, an art dealer who had galleries in

Munich and Lucerne. Ringling's wife, Mable, died that year, and it seems he threw himself

into collecting as a diversion from his grief, buying about 80 paintings. Ringling and

Bohler met in 1922 or 1923 and, until 1931, collaborated on many purchases. During those

years, Ringling acquired thousands of works of art, including more than 600 paintings by

Old Masters. They all ended up in the museum he built next to Ca d'Zan, his palatial home

on Sarasota Bay. Ringling died in 1936, almost broke, but he held on to his dream to give

the museum to the state of Florida.

Like the painting itself, we don't know much about its purchase, because most of

Ringling's records in Sarasota vanished after his death and Bohler's were scattered and

lost during World War II. But Linda McKee, the museum's librarian,

believes the collector probably paid only several hundred dollars for it, compared to the

thousands he would spend on more important artists.

Look at and Play with the Interactive

painting, explaining some of the symbols

|